Does your organization “think product”?

A pragmatic and non-dogmatic approach to product management, that helps companies generate and capture more value from their users.

Product management has popularized a set of principles that have greatly benefitted certain technology companies in terms of creating and capturing value from their users. These companies, which I call the “Think Product” companies, have embraced customer-centric practices, evidenced-based decisions, and a strong (and measurable) definition of success.

We will explore some practices that thinking product embodies and that are beneficial to the whole organization, such as:

- being customer-centric

- running by evidence and product discovery (without excess)

- being driven by a solid (and measurable) definition of success

- counting on the whole organization, not only the product teams, to do so

The overuse of certain buzzwords and an overreliance on frameworks (which I refer to as “Product Fundamentalism”) has led to a divide between product practitioners and the broader business community. We will examine some jargon-heavy concepts, like “Product Led Growth” (PLG), and why they aren’t always in the interest of the business or the wider product community.

It’s worth noting that throughout this article, the term “product” refers to any artifact created and delivered by a company to its users, allowing the business to generate revenue, whether that’s a physical good, a digital product like a SaaS, Web platforms or e-commerce and marketplaces. It can also be any other kind of service that addresses more than one customer and can be offered at scale.

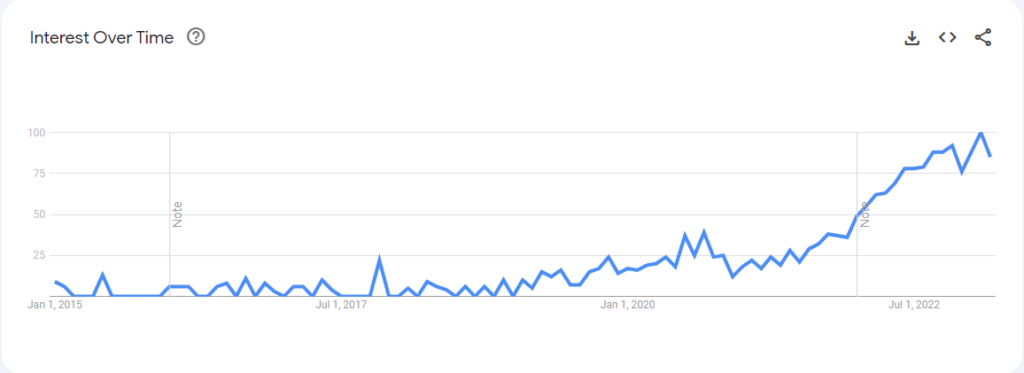

The product management hype

There is no easy way to say this without offending some “product managers” or “product gurus,” but it has to be said: the escalation of product management jargon is becoming challenging to swallow. The hype terms in product management are on a historical high. I believe that the time has come to break this taboo and to talk about this topic with no complaisance.

Product management has been a well-established domain for decades. When the digital and Saas economy started to grow exponentially, around 2010, agile, lean practices, and customer-centricity, were soon “adopted” by product management and gave product people a strong presence in business discussions and up to the C-suite. This has been extremely beneficial, both for companies and for product practitioners. But things have gone a bit out of control.

A few years later, catchy new buzzwords are making their way and increasingly dominating product management discussions: while they sound impressive, many of these new phrases are simply old ideas in new bottles, at best. Or vague, empty concepts, most of the time. A few “hype terms” that are currently:

- PLG / Product Led Growth – that’s my “favorite” one. “Your product is not selling? That’s because you’re counting only on sales! Your product shall enable sales!” … how comes we didn’t think about this before! Is this anything new? No! A product that enables its sales is just table stakes, and something that any PM has been running with for the last 20 years. Are we hearing any concrete and innovative ways to do this among all the buzz? Not really.

- Product Operations: Nobody really agrees on what it is, but it seems we can’t really live without it.

It is time to clear the air and acknowledge that the hype term in product management is at an all-time high. This is not helping to cut the discussion to the bone and is almost degenerating into a self-referencing loop of compliance among product practitioners.

I see that I am not the only one feeling this creep, with more and more product practitioners feeling that this is going too far (Jens wrote an article already a few years ago about it), and there are many discussions on social platforms.

The result? Instead of creating empathy and a healthy osmosis between the (positive) practices in product management and the rest of the organizations, the reality is heading in the opposite direction. … and it looks clear that we aren’t doing anything to help bridge the gap between the product community and the business. On the contrary, trying to elevate the product as “king of the world” (just think about the sentence we still hear “Product Manager is the CEO of the product”) is just making this gap deeper.

Similarly, a crowd of framework creators, consultants, and agile/lean/product coaches, has been increasingly pushing for the adoption of new frameworks as the only way of working. You may have heard sentences like

- “Your teams are too slow? That’s because you’re not doing agile!“ or

- “you’re not implementing Scrum well enough!” or even

- “that’s because you have Product Owners and not Product Managers!”

All this is what I call “Product fundamentalism.” A series of positive elements and concepts that, taken to an extreme (and sometimes stubborn) implementation, do more evil than good.

Bridging the gap: how “thinking product” helps the business. Really.

So, I’d like to start with an observation and propose a slightly different way of approaching all this:

- Product is an important element to create and capture value but is not the (only) engine of a company (or of growth)

- Product people are NOT the boss. The company is not led by product.

- Yet, a way of thinking based on practices that have proven useful for product management can definitely have a wider positive impact on the organization

I refer to these principles collectively as “thinking product”, as a set of practices that can help build a sustainable and flourishing business, and where the product can work as a catalyzer of the essence of the company: creating value and capturing it. Nothing more, nothing less. It’s the job and the goal of the whole organization, not only product management, to seek:

- More predictability despite the unknown. This requires a structured approach to discovery, yet without overdoing it.

- Faster go-to-value. Generating waste is not an option, and cutting to the bone with an interactive approach is a concept that resonates well beyond product organizations.

- Happy customers, happy business. A customer-centric approach based on continuous, unbiased, data-based observations is the only guarantee to align the two. Although, this doesn’t justify any “paralysis by analysis” on the excuse of “product discovery”.

- Leveraging great talents by giving them the freedom to operate. However, there can be no such latitude without clear goals, success metrics, and strategies for the product and the business.

- And all in all, an organization capable of generating (and collecting) more value for and from its users.

Does this apply only to “tech giants”? Not at all, and I was very happy to discover that this way of thinking is spilling over even to more traditional industries such as journalism.

This is what is in it for the organizations that decide to “think product.” And Product managers, although not the “ultimate boss,” sit in a privileged position to ignite and enable these benefits throughout the organization.

Thinking product

Concretely, there are a few practices that have been “adopted” by product management and that can be extended broadly in organizations:

Agility & Lean Management: Reducing the risk of the unknown by working on small batches whose impact can be verified in reality with relatively little effort. These concepts are well established in product management and can extend broader in the company. However, it’s important to keep this within reason and avoid any meaningless stretches. If there is no risk to be mitigated and you know what you’re doing, you probably don’t need to be “agile” at all costs and bring “sprints” to every department. Does the finance department have to work in two-week cycles? mmm…

Objectives, OKR, and success definition: One can only iterate toward success if the latter is clearly defined. Sound product metrics are a good start, and products are thought to be measured in their usage and their impact. Extending this practice to other areas of the company is the next step.

Hypotheses-driven iterations: Exploring broad/new business opportunities can be greatly facilitated by spelling out what is the underlying hypothesis one is trying to test. I usually also suggest clearly attaching hypotheses to each element you have on the roadmap; this forces a stress test by ensuring that (if your hypothesis stands true) what you have planned could contribute to your goals and is not just coming out of nowhere.

Product Discovery: Understanding customers’ needs and behaviors does not only matter to product managers. Sales, support, and virtually any team have a piece of the puzzle to contribute. This is another slippery and abused one, though, as it becomes very easy to overdo; you don’t need to discover what you (or the rest of the organization) already know. And long, unclear, blanket “discovery” activities in your roadmap are the best way to dig an even larger gap between product and the business. In other words, to be used carefully.

Thinking in terms of value for the business and value for the customer. Product people like to say they “create products that customers love.” However, any organizational boundary you may integrate into this statement would be an artificial one, and your customers will love (or not) the whole experience with your company. This love does not start and end with the product but spans at least the sales, payment, and overall brand and support experience. To name a few.

Team empowerment, autonomy, and accountability: again, this can only be achieved if success metrics and product (actually, company) strategy are clearly defined. By far, the most common reason I found for teams not being autonomous is the lack of understanding and agreement around the goal they’re supposed to work toward. And yes, setting meaningful goals and metrics is hard!

These practices are common in product management, and that’s what I call collectively “thinking product.” But they’re not uniquely confined to product management and can be applied throughout the organization to make the company “think product.”

Too many companies still hire one product manager/owner and call it a day, hoping this will make the organization “think product”. Product management can be crucial in facilitating these practices rather than forcing them upon others. However, a meaningful change in the direction of a “product thinking” organization has to come from the top and is a strategic move. More about the role of a CPO in the next article.

Conclusions

Thinking product has material benefits for modern organizations and is something that involves the whole business and not the product organization alone. It’s not about hiring one product manager or two, but it is a real shift in paradigm that has to get a strong drive from the very top of the organization. At the same time, the recent “product fundamentalism” in the product management circle, based on hype and mostly meaningless terms, has created a gap between product practitioners and the rest of the business.

This article provides a pragmatic and non-dogmatic approach to applying the most critical product principles, such as agility, iteration, discovery, and user centricity broadly in the organization. I call this simply “thinking product.”

The subsequent articles in this series will cover why a CPO is essential for any CEO who considers thinking product seriously and when it’s the right time to hire one.

Thanks to Dominique Jost, Büşra Coşkuner, and Jens Kuerschner for the discussions that led to many of my thoughts about thinking-product that I expressed in this article.

My name is Salva, I am a product exec and Senior Partner at Reasonable Product, a boutique Product Advisory Firm.

I write about product pricing, e-commerce/marketplaces, subscription models, and modern product organizations. I mainly engage and work in tech products, including SaaS, Marketplaces, and IoT (Hardware + Software).

My superpower is to move between ambiguity (as in creativity, innovation, opportunity, and ‘thinking out of the box’) and structure (as in ‘getting things done’ and getting real impact).

I am firmly convinced that you can help others only if you have lived the same challenges: I have been lucky enough to practice product leadership in companies of different sizes and with different product maturity. Doing product right is hard: I felt the pain myself and developed my methods to get to efficient product teams that produce meaningful work.