Product Monetization Guide: The Pricing Strategy

If there is one common element in the way pricing is addressed by a multitude of companies, smaller or larger, is the fact that pricing is often addressed as a last-minute side detail (at best) or as a simple guess (at worst).

However, price is not only the money you capture from selling your product (or service). It is the best marketing element of your offering, your single biggest product growth tool, and the most important feature of your product. So, why isn’t pricing taking the same headspace as R&D topics. or being looked at with the same scientific eyes of Data Science? Why do people often prefer deferring pricing discussions and eventually settling them in a rush on the basis of gut feeling?

The reality is that pricing is a tough discussion. Many companies find it difficult to decide where to start and get stuck with tactics and details that won’t really move the needle. Depending on the culture, “talking money” may even be seen as intimidating. Whatever the price you will set for your product, it will be material to attract some customers and will inevitably turn down others.

But the good news is that there is a real opportunity to have pricing working for your business: by addressing it actively rather than passively, with confidence and knowledge rather than by accident, and regularly rather than just during crises. As long as you start on solid bases, and you build your strategy with a structured approach, the right pricing strategy may become the best feature of your product.

In the next paragraphs, we will go through some practical tools you can use to approach pricing discussions with confidence and decide which pricing strategy is the right one for your product in your particular market, at a specific moment.

The biggest misconception:

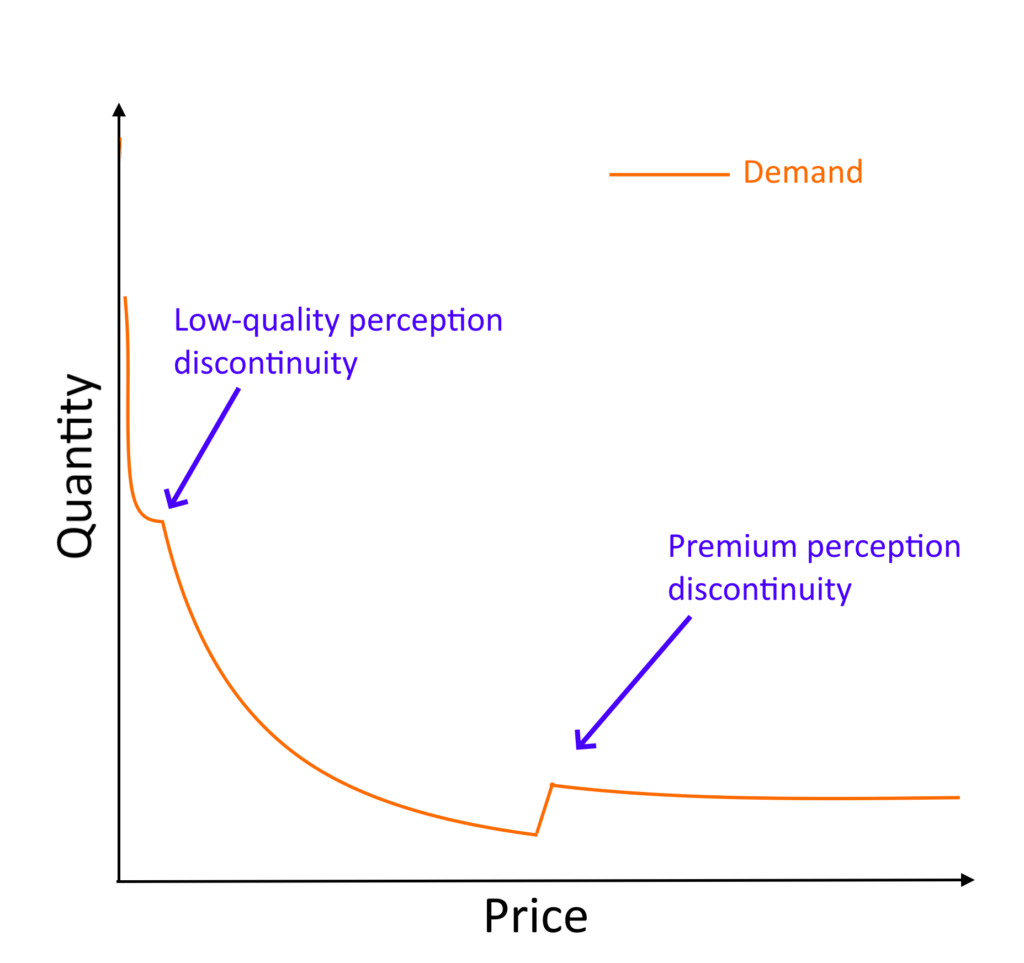

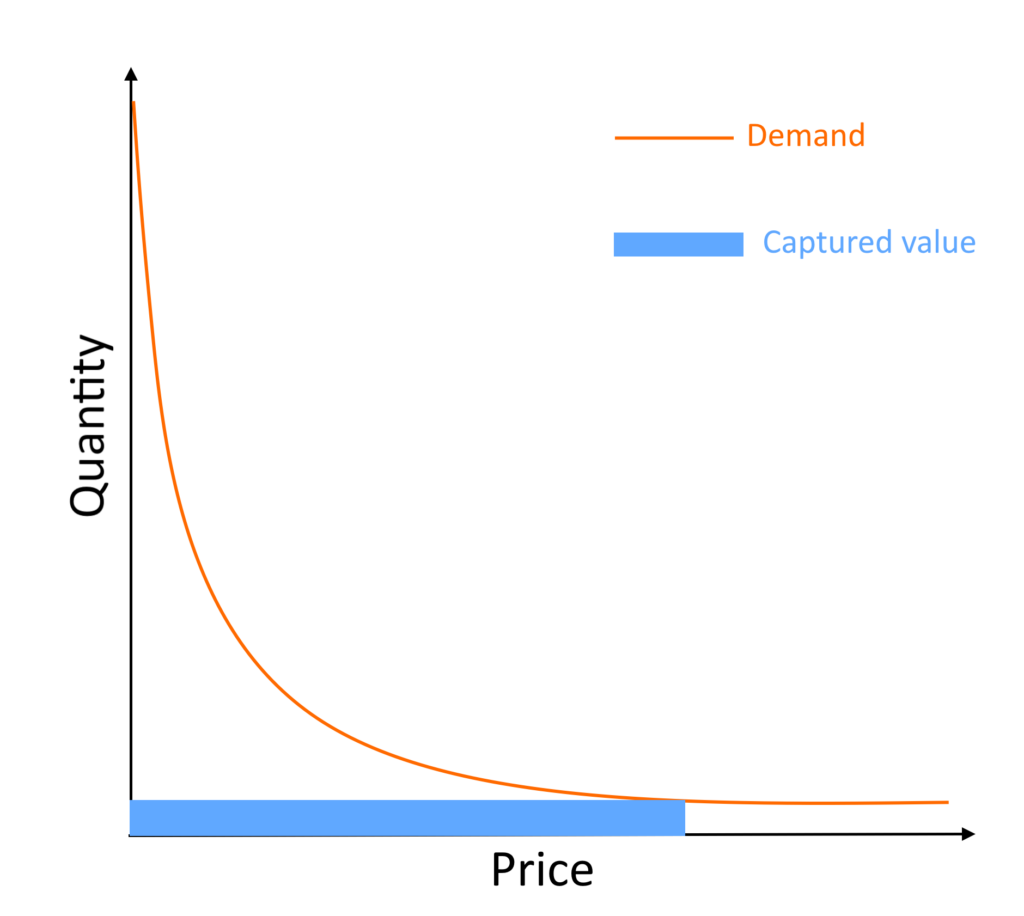

We are all very familiar with the concept of the “demand curve”. The demand curve is a graphical representation of the evolution of the demand for a given product, as a function of price. The higher the price, the lower the number of people ready to buy your product. Sounds logical.

Instinctively, we imagine that a product that is “selling poorly” (i.e. to a few people), is priced too high and needs a downward price correction to sell to a wider audience. While this is true in the absolute theory of the books, the reality is much more complicated. The price itself has a direct influence on the positioning and on the perceived value of the product, which modifies in his turn the shape of the curve. A product priced “too low” may reduce the demand even further, and vice-versa. In other words, the price itself can “move” people from one demand curve to another which creates “discontinuities” on the theoretical demand curve.

Not only do prices enter into play at payment time (do I hit “pay” or not…). By looking at pricing as a communication means and a “feature” of your product, it’s easy to understand that it can be a tool to play with to differentiate and communicate the value of your products to your customers. Think about your website: where do your users go when they want to understand clearly WHAT they are going to buy and WHAT they will get out of it and HOW your position yourself compared to the competition? Yes, it’s the pricing page!

Starting from the beginning: fixing the basics

If you made it here, you are probably aware of the importance of getting your price right. In many of the pricing discussions I get involved in, usually, the first question I hear is “What price shall I charge?”. Or “Is my price right?”.

Unfortunately, that’s not a question that can be answered alone. Pricing builds on some fundamental blocks that you need to figure out before jumping to the pricing board. Here are a few things I usually check before I start working on pricing:

- Value proposition & Drivers: Is it clear for your customers AND for yourself why they’re buying your product? What are they trying to achieve with it (the “job to be done”) and how your product is contributing to their objective?

- Positioning & Alternatives: What are the other alternatives your customers have? Is there any competition and how would you like your product to be positioned among the other choices? If so, which part of the market would you like to carve out for yourself (premium/luxury; good value for money (smart choice); budget…).

- Differentiators: Are you able to differentiate from your competitors or alternatives on the basis of the features/value delivered by your product? Or, to the opposite, would you like to use your pricing strategy as a differentiator (for instance, provide more flexible pricing models?)

- Value Unit: Pricing strategies are about defining HOW you will set your pricing between two hard limits (variable costs and value). However, to be able to set your pricing you have to decide on which basis you will be charging your customers. Think about a SaaS service: is it going to be based on the number of users? Per month or per usage?

- What is the goal you are trying to achieve by adjusting pricing? Are you trying to extract more margin from each sale? To penetrate a new market? There is no single best pricing strategy, and the important is to find the right one for your product, in the context of your objectives.

It should be clear by now: pricing shall be dealt with a cold mind. Without the right tools and the right approach, the risk of overreacting to market corrections and leaving money on the table, or just getting into a negative vicious circle is very high.

So, before you go on the pricing drawing board, be sure you have your basic product homework done!

Get yourself a pricing strategy

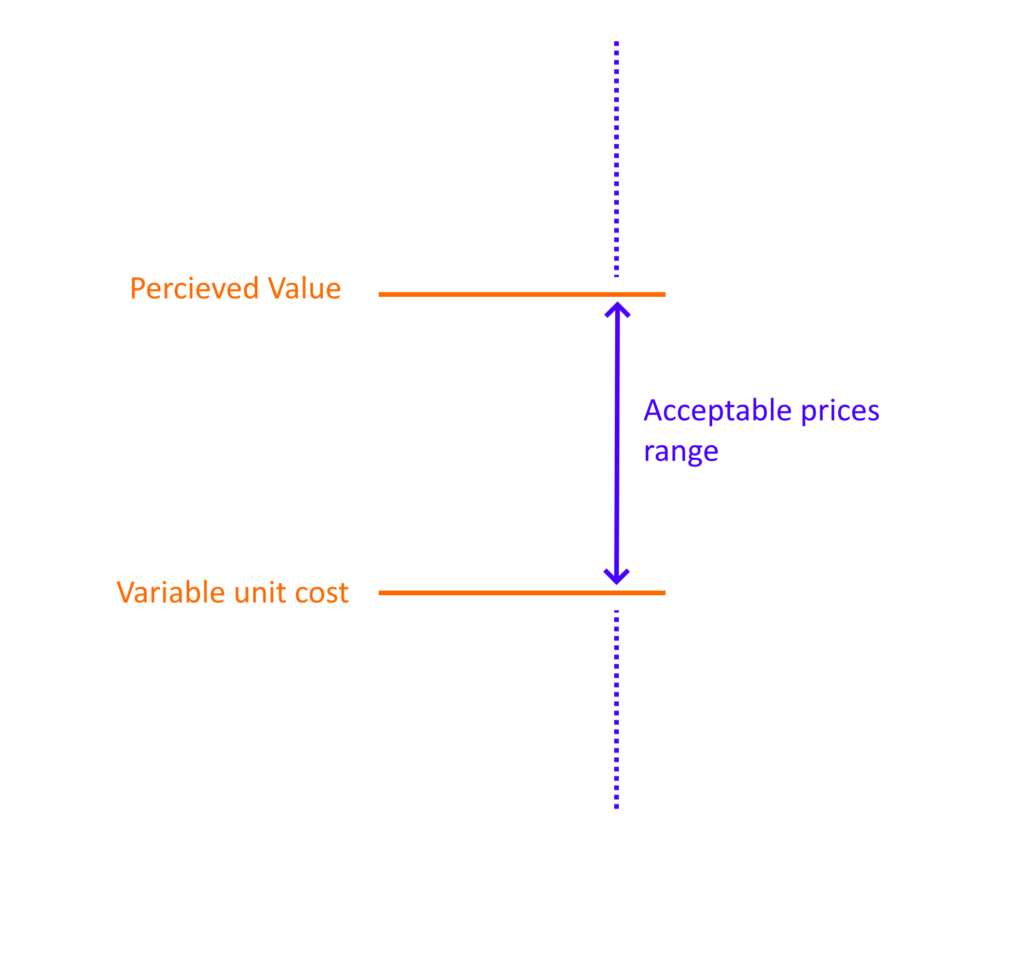

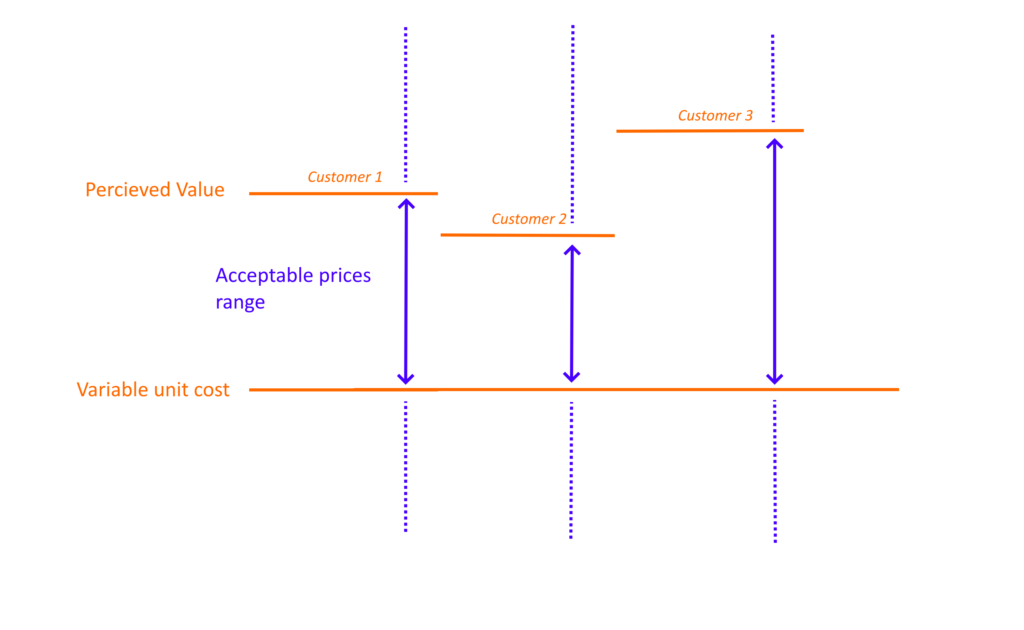

The whole thing about a pricing strategy is to decide how you will set your ballpark pricing between two hard limits: your variable unit costs and the value perceived by the customer.

Well, this is not entirely true. In some cases, you may go e bit lower (aggressive pricing/predatory pricing), or a little above (skimming pricing/premium pricing) (more about this in the next section). While variable unit costs are usually constant, the “value” is subjective and dependent on each one of your customers. Therefore, the ceiling limit is not uniquely defined (more about this in the “value-based pricing” and “differentiated pricing” sections below).

As a general rule, you have a certain range you can set your pricing within, and figuring out the right approach (not the exact point) for your product is what we call the pricing strategy. A pricing strategy is NOT about debating the exact details of your pricing points.

Note: In SaaS, you have a lot of latitude with pricing because usually, the intrinsic marginal cost of a unit is low to zero. This does not mean that your variable costs are zero (think about your acquisition cost for instance).

All your Pricing Strategy options:

- Cost plus or cost-based pricing: This is probably the simplest pricing strategy you can think about. You look into your variable unit cost, you decide on a markup or margin you want to make, and you add them up to determine your selling price. It is easy to implement and it ensures mathematically that you will make a profit on each of your sales. However, Cost Plus pricing is rarely the best option: with no hook to the value of your product, nor to the context of your market it’s a bit like shooting in the dark.

- Penetration pricing: If you’re entering a new (crowded) market, pricing may be a way to differentiate yourself from the competition by offering your products at a price that is clearly lower than the competition, at least at the beginning and until you have established your brand and presence. With Penetration pricing, you are trying to “get noticed” and get some loyal customers that will stay with you once you will raise your prices. Think about Easyjet at the beginning of their journey: they were once known to have cheaper prices. Although they keep the “low-cost” branding, their prices are now aligned with the competition (Competition pricing), they have a well-developed “Add-on” approach and they intensively use Dynamic pricing to capture additional revenue. Also, don’t confuse Penetration Pricing (where your prices are lower than the competition to enter the market), with Budget positioning (where your prices are constantly lower than the competition to capture a different segment of the market).

- Price Skimming: You can look at Price Skimming as the “opposite” of Penetration Pricing. Pricing Skimming is especially useful in new markets where no to little competition exists. By having something unique to sell, you set your prices high in order to maximize your profit by first addressing the part of the market with the highest willingness to pay. In other words, with Price Skimming you are ok temporarily “neglecting” the lower-paying segments and focusing on the higher-paying ones, to avoid the risk of cannibalization. Over time, competition will enter or you will simply want to expand and capture the rest of the market. You will do this by adapting your prices and moving on the demand curve. Be careful though with price Skimming as it can come across as arrogant and “outrageous” and ultimately have an impact on the brand.

- Competition/Market pricing: In a market where you are not the only player you cannot ignore the competition. In Competition Pricing, your prices are set by looking at what your competitors are doing (reference prices) and then working on relatively little variations from those depending on your positioning. Competition Pricing is not something you choose to do, but rather something you have to live with, a consequence of a crowded market in which you are not able to hugely differentiate or become “incomparable”. Therefore, before “settling” for a price based on one of your competitors, all your efforts need to go into the differentiation of your value proposition, which you can do not only by means of features but also through a different business model or revenue model (example: changing the value/pricing metric unit). Also, I suggest that don’t look into Premium or Budget/Economy pricing as separate pricing strategies, but rather as positioning you will get as part of your Competition pricing.

- Value-based. Value-based pricing is considered the “holy grail” of pricing, as it allows you to get as close as possible to your upper limit: what the user believes your product is worth. In value-based pricing, you “forget” about your unit costs and about your competition, and you focus on the value you’re delivering to your customers. In other words, you try to answer the question “How much is my product/service worth to my customers”? Can I quantify the time they will be saved thanks to my product? Or the additional revenue they will make with it? The advantage of this approach, besides maximizing your margins, is that it forces you to understand your customers, their drivers, and why they come to you. The catch here is that you cannot go for value-based pricing unless you are able to differentiate your products from your competitors. Even if you’re delivering great value, if the market is ready to pay less for this value, you will not be able to succeed with this strategy. Value-based pricing is a great tool to grow your revenue while ensuring that your product stays relevant for your customers, so I can’t recommend enough to go for it… All the preparation work needed to do so (a deep understanding of your customers, strong differentiation,… ) is great for your products on so many levels.

- Performance-based pricing or Outcome-based pricing: Performance-based pricing is kind of a “Value-based pricing on steroids”. Here, the price you capture is not just related to a hypothetical value you are generating for your customer but is directly linked to the benefit you are creating for them. In other words, what you get paid is directly linked to the results you are bringing to your customers. Very typical in transactional businesses, two typical examples of Performance-based pricing are revenue sharing and commissions. The clear advantage of this model is that your customer is ready to share with you a larger part of the product worth countervalue, in exchange for your “skin in the game”. Of course, the catch is that you have to perform to be paid, which requires you to be sure of your product AND of the business/usage that your customer will do of it.

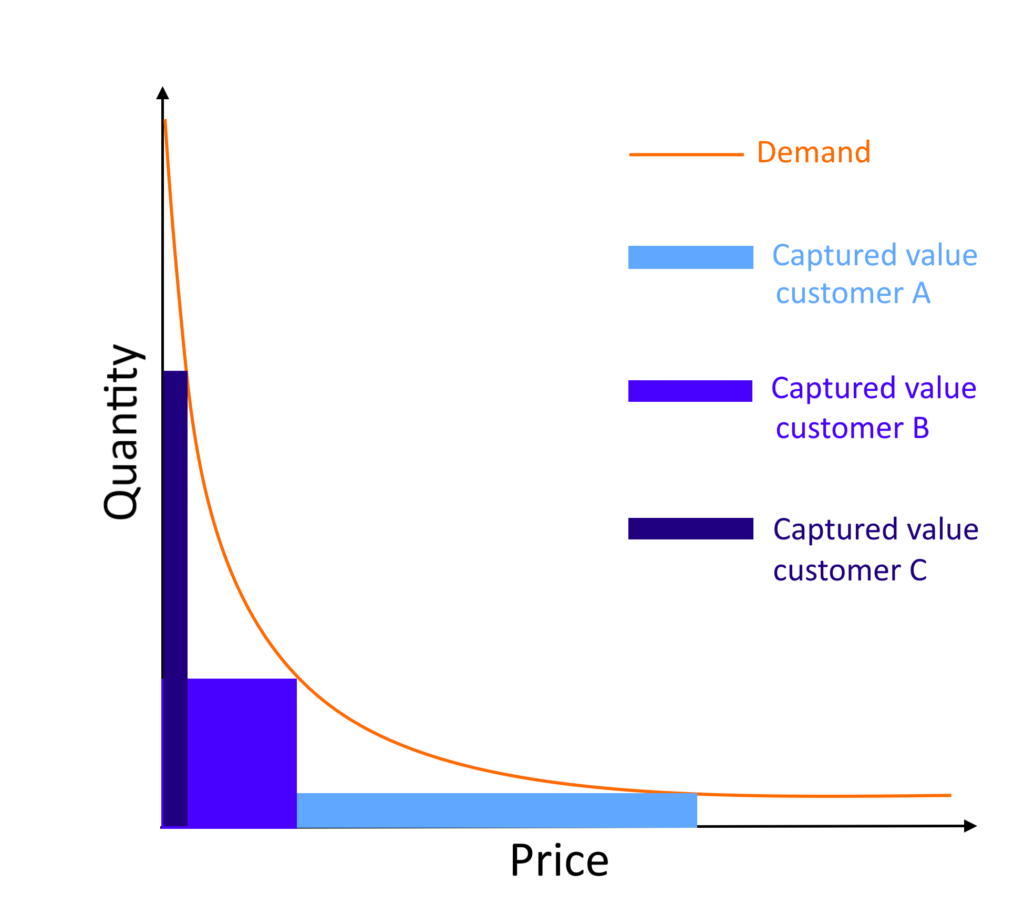

- Differential pricing: In Differential pricing you try to maximize the value you capture, by adapting your price to the individual willingness to pay your customers (to some extent, the fact of having 3 different plans in your offer is a form of differential pricing because it helps you serve different segments of the market with different needs and willingness to pay). The biggest risk here is cannibalization, where a customer with a higher willingness to pay “settles” for a cheaper product of yours. That’s where discrimination comes into play, to ensure your offers really “fit” each one of your customer profiles and that the offer itself helps you “discriminate” your customers in a way that they’re not tempted to get an offer that is not tailored to them (and to their willingness to pay). Auctions are the “ultimate” way to perform price discrimination, by ensuring your customers are bidding the maximum they’re ready to pay.

- Dynamic Pricing: Not only do two different individuals may have different willingness to pay, but the same individual may have a different willingness to pay depending on the context. Think about an umbrella: how much are you willing to pay for it on a sunny day, in a supermarket… versus how much you will pay if you’re caught by rain by surprise in the street, dressed up for an important meeting! With dynamic pricing, the price of your product evolves as a function of the willingness to pay off each one of your users: usually elements such as time, weather, distance, and location are all potential “proxies” to estimate this willingness to pay. You can look at Dynamic pricing as a complement to Differential pricing. In the latter price evolves as a function of your customer, while in the first one as a function of additional contextual elements.

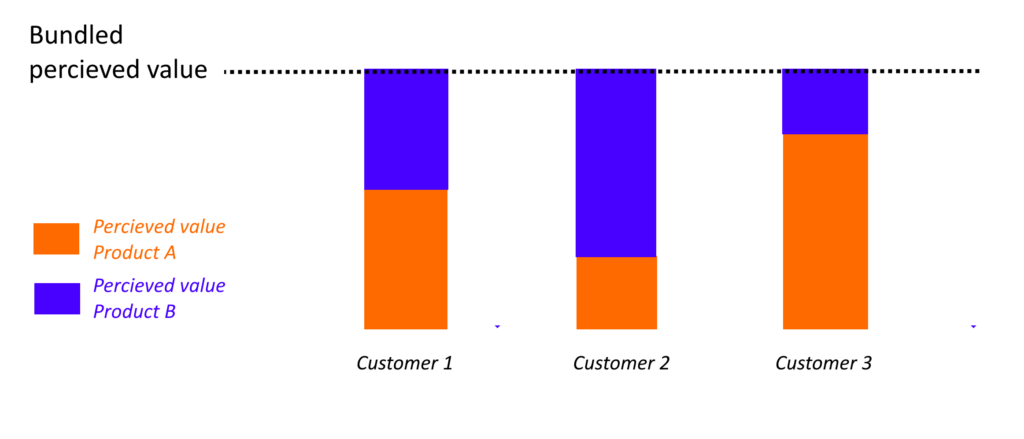

- Bundle pricing: sometimes each one of your products may have a very different value for your different customers but, somehow, the set of several products as a whole may have a similar value. Imagine you’re selling two products A and B. Some of your customers are ready to pay a certain price for A and some others will find this price expensive. However, the same customers that find A expensive, see a lot of value in B and less in A. If you sell A + B together (at a total price that satisfies both categories of customers), you will be able to capture a larger market share and maximize your profit, without cannibalizing the individual products. Bundles are very common in SaaS products and I will write a separate article on the topic, so stay tuned and be sure to subscribe to my newsletter to be among the first ones informed!

Some variants of the Penetration Pricing strategy

There are also two specific variants of Penetration Pricing that are worth mentioning:

- Crowdfunding pricing: Even though usually the market addressed by the crowdfunding project is a new market, Crowdfunding projects tend to offer lower-than-expected pricing in exchange for the support of the customers to create the market and the demand for a new product. As in Penetration pricing, the strategy includes a price increase at a later stage, once the market is mature and the positioning of the new entrant is established.

- Predatory Pricing: is a variant of Penetration pricing where the company aggressively reduces the prices, to a level that is almost “unhealthy” for the whole market to win the long term and with the objective of having the competitors run out of the game (or out of cash…). Once the competitive landscape is free, the company would then increase the prices as in Penetration pricing. Note that Predatory pricing is illegal in some legislations, and may be considered an unfair competitive practice.

At this stage, you will still have some questions such as: shall we have a loss leader? One or three pricing plans? Shall we end our prices in .0 or .99? All these are very valid questions but are tactics and not a pricing strategy. Decide and develop your pricing strategy first, and only then move to the tactics and details. I will write a separate article on pricing tactics, so stay tuned and be sure to subscribe to my newsletter to be among the first ones informed!

The right time to get yourself a pricing strategy

In my experience, the majority of companies start looking at prices when something suddenly changes and they feel they need to urgently “adapt”. Sometimes because the revenue numbers are not there. In other cases because of a new competitor entering the market. Or because an investor is asking. All these are valid reasons to re-think your pricing strategy, but there is more. Hopefully, the list below will help you approach this subject actively rather than passively:

- At product launch: you really want to look strategically into pricing from the very beginning. If you lose an opportunity at launch, it may be very difficult to recover later. Also, your positioning will be “hooked” in your customers’ minds, and undoing it may prove hard. Are you creating a new category? Potentially Skimming Pricing may help you capture more value from the very beginning. Are you very clear about the measurable benefits you will bring to your customers? Performance-based pricing may be a good option to maximize profits while reducing the risk felt by your prospects.

- New products in your offer: That’s a good occasion to look at the bigger picture. How do they fit together? Are they positioned in a way that helps you differentiate customers by their willingness to pay by discrimination? Is there a new opportunity for bundling and capturing the different willingness to pay more consistently?

- Changes in the market: Is there a new entrant on the market undercutting your prices? This may be the occasion to review your positioning and try to cut a more “premium” share of the market or to play with Dynamic pricing to get the best of both worlds.

- Regularly. That’s my suggestion. Don’t wait for something “special” to happen. You should be looking at your pricing on a regular basis. Depending on your business and your market, you may have continuous pricing experimentation ongoing all the time (tactical level) while looking at the strategy itself on a yearly basis or so.

Bonus: The wrong way to address pricing

If you made it here, I’d also like to give you a few ammunitions against some very common pitfalls I’ve seen. We all tend to fall into these traps and, by knowing them, you will hopefully be able to identify them before they bring you off-road. Whether they’re coming from you, or from a bad framing of a pricing project you’re in:

- The “good-better-best” trap. We’re all used to seeing pricing plans such as “good-better-best” (or bronze, silver, gold). Such plans can be a tool to build your offering, but be aware of starting from there! Starting your strategy by building your value metric AND strategy first and only then work on your plans (usual indicators you’re in the trap: “We have a strategy, we want to create a silver and a gold plan”)

- The “price hook” trap. This happens when you get a price in mind and try to build your positioning around it. When reworking a pricing strategy the risk is that you are still hooked into the current pricing (or one of your competitors) and you don’t address the problem from a fresh perspective. Start on a blank piece of paper, rather than “reverse engineering” your strategy from the price you’d like to hit! (usual indicators you’re in the trap: “We have to get a 19$ offer”)

- Get stuck in the details. Don’t waste time debating $100 vs. $105, nor if ending prices by .0 or .99. None of them will have a stronger impact than getting the fundamentals (positioning, value metric, and pricing strategy) right from the start! (usual indicators you’re in the trap: discussing anything more granular than orders of magnitude before the strategy is set and agreed upon)

Special Tip: get the FREE Product monetization Canva

Do you want a simple way to look at all the Pricing elements at once? Download the free Product Monetization Canvas

My name is Salva, I am a product exec and Senior Partner at Reasonable Product, a boutique Product Advisory Firm.

I write about product pricing, e-commerce/marketplaces, subscription models, and modern product organizations. I mainly engage and work in tech products, including SaaS, Marketplaces, and IoT (Hardware + Software).

My superpower is to move between ambiguity (as in creativity, innovation, opportunity, and ‘thinking out of the box’) and structure (as in ‘getting things done’ and getting real impact).

I am firmly convinced that you can help others only if you have lived the same challenges: I have been lucky enough to practice product leadership in companies of different sizes and with different product maturity. Doing product right is hard: I felt the pain myself and developed my methods to get to efficient product teams that produce meaningful work.