A Product & UX look into pricing: Netflix removes account sharing

Netflix is the market leader in streamed entertainment. Part of its success has been built thanks to a smooth experience, accessible prices, and billing flexibility (compared to pay-tv subscriptions). Exclusive content productions have come into play at a later stage, and have been material to acquire and retain subscribers to the platform.

While Netflix has been historically very tolerant of a practice called “accounts sharing” practices, they believe it’s now time that these users start to pay their own subscriptions. This change has been recently communicated by the company and has been largely relayed by the press. Despite this noise, I couldn’t find any deeper analysis of the impact on the product, the user experience, and the economics of this move. Does it actually make as sense as it may look at a first glance?

In this article, I will try to go through the different implications of this move, based on my experience in the subscription businesses. To be clear, I do respect and share Netflix’s willingness to monetize its users a lot. At the same time, I will argue that the path they’re taking seems somehow inspired by the rush and could have unexpected consequences on their own product positioning.

How did we get there?

Netflix is almost synonymous with streaming content. Despite growing competition coming from other streaming providers (Amazon Prime, …) and the content providers going “directly to the consumer” (ESPN, Disney+,…), Netflix still owns the largest part of the cake.

But how did they build up this success, and where did they capture their users from? I won’t start telling the story of Netflix moving from the DVD into the online business, which is a very well-known story in management and innovation books. But let’s go back a few years and see how Netflix built its current customer base.

I’ve been working in the anti-piracy industry for almost a decade. Back in 2010, we were very busy fighting “content download” piracy, and we were moved by a willingness to build a healthy environment for content creators, where their work could be recognized and monetized fairly. In other words, we were using the “stick” to remove illegal content from the net, and entice people to purchase legitimate content. At that moment, it was mainly through DVD/Blue Rays, and sometimes via Pay-TV and VOD (Video on Demand) offers.

UX as leverage, friendly pricing on top.

I may be biased by my “product and UX” hat, but one of the major changes I observed in the entertainment industry recently, and in particular with respect to piracy habits, has been the different paradigm that Netflix introduced about a decade ago. While we were busy using our stick, Netflix introduced for the first time the concept of improving the overall experience of viewers, from content discovery to content consumption. In other words, they tackled the problem with a “carrot”, rather than a “stick”: they just made access to legit content so much easier and sleek than it used to be, that getting a Netflix subscription instead of downloading illegal content became almost a no-brainer.

Add to this, a business model based on an accessible and universal fee (about 10 USD/month back then), an “all you can watch” model, and here is how you smartly transition an issue into an opportunity.

I am not saying that nobody is downloading illegal content anymore; but a segment of the population that was on “the edge”, found it very easy to transition to a legal, affordable, and user-friendly platform like Netflix.

10 years of price increases

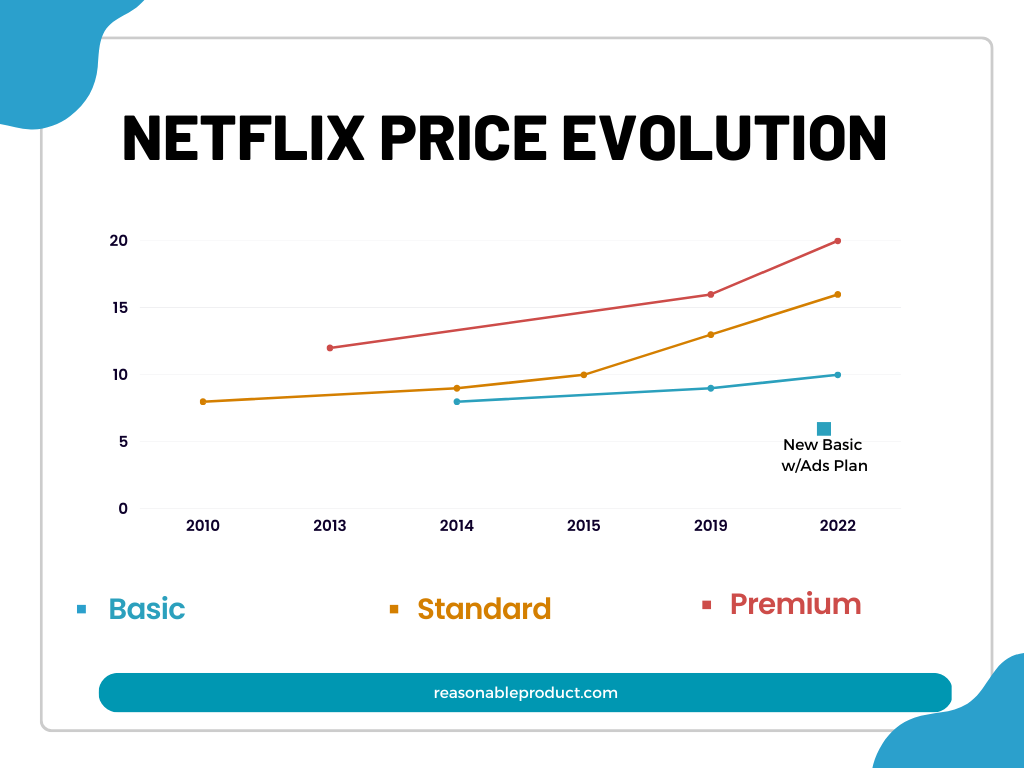

Fast forward 10 years later, and a few price increases that Netflix pushed on its users.

Despite the increasing competition by new entrants, such as Amazon Prime, sometimes up to 50% cheaper, Netflix has been able to increase its price continuously since the beginning of its journey.

And although some of their raises may see seem a bit “audacious”, a savvy differentiation and fencing on the packages (currently ranging between 1.9 USD and 25 USD/month depending on the plan and the country – https://www.comparitech.com/blog/vpn-privacy/countries-netflix-cost/), and a heavily-country-dependent pricing strategy made these increases “material but acceptable” for most.

Although all these increases may seem aggressive when you look at the evolution on the graph, the reality is that they’ve been pretty organic until now. The same user base, “happy” to pay 6.99 USD at the beginning, has been spoiled with additional original content. Netflix has introduced different product tiers (mainly differentiated by the maximum video resolution and by the number of users who can watch at the same time). Today, the entry price has not evolved much from the beginning, while a segment that is “happy to pay a premium” can pay up to 19.99 USD/month.

The reason why these price increases have been successful so far:

- Price increases have been “organic”. Audacious, but introduced smoothly

- The value was “clear” to the users, with additional premium content added to “justify” the increase and fence the packages

- Original content has developed a real “addiction”. If you switch, you just lose your latest TV show. Scary!

- The user base was ready to pay, from day one.

- The value of the premium packages, including the fact that the premium tiers allow having up to 5 concurrent users streaming. Hem, did you say account sharing?

Let’s have a look at these elements one by one, and remember especially the last two points, as they will be key to our analysis.

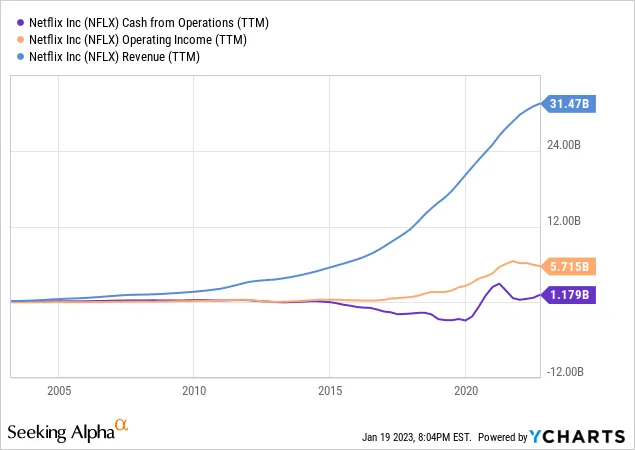

Netflix, who’s been injecting billions of dollars into content rights and original productions. This investment started around the years when “House of Cards” was launched in 2012. While this has represented an important expenditure for Netflix, it is clear how this has represented a key aspect of their growth. On this topic, I found the explanations of Bertrand Seguin about the impact of these investments on Netflix Cashflow extremely helpful.

As you can see in this graph, it’s only recently that the net investment in content has started to contribute positively to the cash from operations.

What is changing now?

As we already observed, one of the “selling points” of Netflix premium plans is the possibility to stream different content to multiple devices at the same time (up to 4). In other words, up to 4 different users (or groups of users) can connect at the same time, using the same username and password, and watch 4 different shows/movies on 4 different devices (tv, tablets,…) under the umbrella (and cost) of the same subscription.

This feature was thought to let customers use Netflix on multiple devices in the same physical location (imagine, kids watching TV in the living room and parents on a tablet in another room). Needless to say, many users have been “abusing” this feature for years and have been sharing their credentials (username and password) well outside the household, for instance with family, friends, and acquaintances living in different locations or even countries.

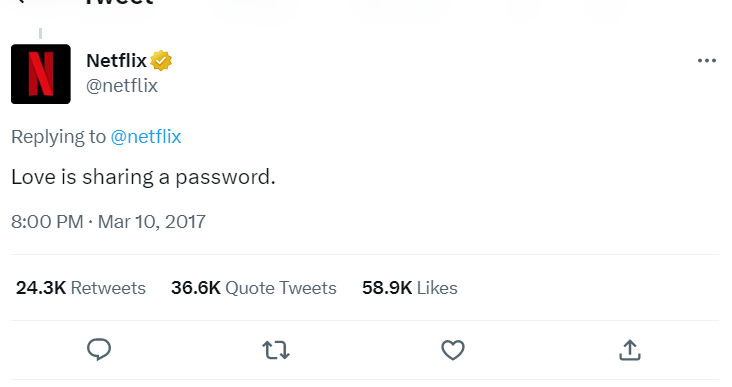

Netflix has been known to be especially “soft” on account-sharing practices until now, up to the point of publicly sharing the famous “Love is sharing a password” tweet in 2017. But it looks like things are changing. Over the past weeks, Netflix has enforced more stringent “anti-account-sharing” rules in the Americas and is now doing the same in Europe.

What will be the effect of this new policy? Let’s go through the details of these changes, and let me explain why I believe this move will have more implications than potentially originally expected.

First of all, let me say that it is legitimate for a business to want to monetize their users, no discussion about this. Netflix is a for-profit company, and they’re accountable to the shareholders for the performance of the business. The question is, how much of a calculated opportunity was it? And was all the necessary preparation work for such a crucial change done? Shall we consider the “tolerated” sharing as a sort of organic “freemium” model they’ve been cultivating until now “on purpose”?

I am not so sure that the previous tolerance was really intentional, nor that the opportunity they’re after now is a natural consequence. Here is why.

A 6B USD dream

Analysts look at the topline and the overall number of subscribers, fine. It is normal and healthy to go and look for more customers, wherever they are. Shared accounts seem a reasonable place to look for untapped opportunities, at least when looking at the problem from a 10.000 feets (company) perspective.

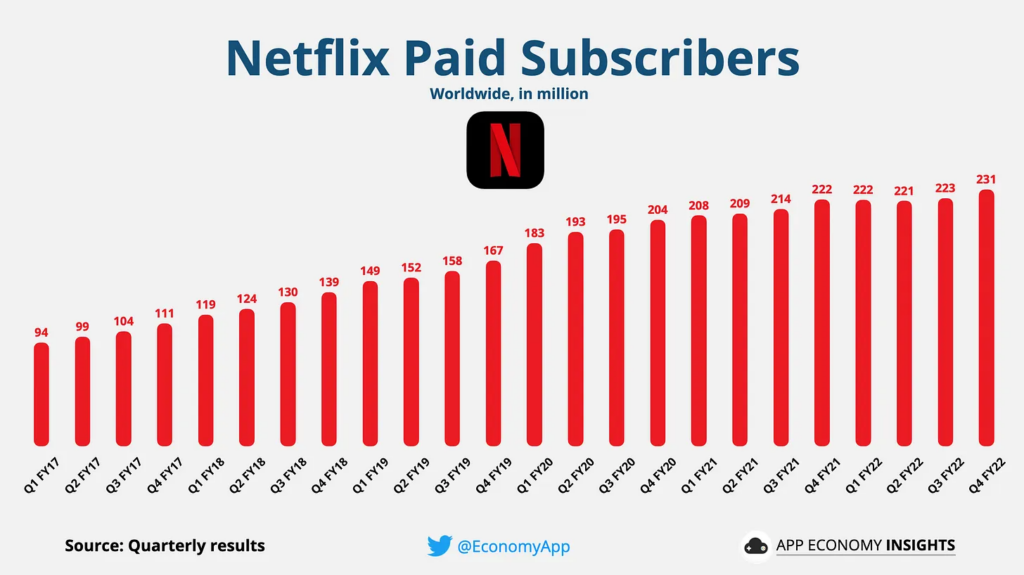

Let’s also add that Netflix had a more than decent 2022 year, outperforming its own forecasts and reaching a whopping 232 M paying subscribers at the end of the year! Not too bad of a start for Ted Sarandos, who recently stepped in as co-CEO alongside Greg Peters.

Let’s start from the Netflix perspective. Netflix assumes that about 100M users are watching their services “for free”, basically pigging back on somebody else’s account. That’s the “size of opportunity”, from their point of view. In other words, the “total addressable market” (TAM) is estimated at 100M users (this is, half of their current paying base). At 5 USD (rough average, more about this later) for these new “dependent subscriptions”, this is a potential uplift of 500M USD/month, or 6B USD/year.

Even for a new CEO that has recently ended a pretty successful year and added 7.66 million users in the last quarter, this is still too good of an opportunity to let it go!

Wow! Really? Well, not too fast!

Converting free users into paying customers

Let’s now look at this from the users’ perspective.

The key question is: will these users convert to pay? How many? At which price point? Is their “willingness to pay” there, or were they just there until and because it was free?

Now, do you remember the two points I made before about the users’ willingness to pay, and how previous increases have been organic and on a customer base that is used to pay?

Let’s now explore this topic in-depth, starting with the way Netflix has managed its freemium model. Yes, in the past there used to be a “try before you buy” model, but in this Netflix has always been somehow ahead of its time and did a great job in selecting users that were ready to pay in the first place. How?

- Netflix has been one of the pioneers of the “credit card needed to start your trial”. When a few years ago the majority of subscription services were happy to give you 7 to 30 days for free just with an email address, Netflix did the “bold” move of asking for a credit card number in the first place. I am sure this led to a smaller conversion rate at the beginning, but the users who converted were more likely to continue after the trial. In a nutshell, they had a clear approach where they “selected their customers”.

- Today, there is no free trial anymore with Netflix. You know the value, the brand is there. If you want it, you pay for it. And, of course, you can cancel anytime.

A brave, but also very rational and successful approach. So, what is the relation with the “account sharing” topic? Well, this “asset” they had until now, a customer base “trained to pay from the beginning” is not something they can leverage with this new category of users, who’ve never been used to paying (or at least not directly). The move that Netflix is starting now, by trying to monetize this new category of users, brings them to a completely new land: the land of monetizing a set of users who’re not willing (or at least used) to pay in the first place. A willingness to pay, sure, but also a user experience topic as we will see.

Keeping the currently paying customers

Another major question is, will the owners of the “main accounts” churn as a consequence of these more stringent rules? In other words, will they consider that the price they’re paying is justified once their “ability to share” the account is removed? Even at a constant subscription price, this is still a price increase for these customers, especially if they are sharing the bill with somebody else. In the same way as Coca-Cola reducing the size of its bottles while keeping the price “label price” (the so-called “Shrinkflation” practice) is performing a hidden price increase, similarly, Netflix removing the “sharing feature”, may just be perceived as a disguised price increase.

Netflix itself considers churn “a possibility”, and it’s worth observing that to some extent one of the major benefits of the “premium plans” has been the possibility of … having multiple streams/users at the same time. A customer who’s been paying until now the Premium plan to get (and perhaps share) his credentials will now have to stop sharing or add about 5 USD more for each user they’re sharing with. It’s easy to see that for most customers, the value of a Premium plan may instantly reduce.

In other words, are there really many users who need 4 parallel streams in the same physical home? Will the other features in the Premium and Standard plan be enough to “fence” against the Basic plan? Clearly, the risk here is to get a massive downgrade of Premium users to cheaper plans… if not a full churn of users altogether.

Why is it a user experience topic: the path to paying

Besides the pure “face price” there is certainly a matter of “habit to pay”. Habit as in “willing”, but also habit as in “finding it familiar”. In other words, these 100M users who have not been used to paying, will have to go through a new process and this will definitely come with friction.

As we saw already, Netflix has been building its success on a “user experience” that spanned from interfaces to the easiness of finding content, to the ubiquity of its presence (Tablet, TV, PC).

To be fair to Netflix, they are indeed doing something more than “using the stick” to convert these “passive users” into paying ones. Here are a few measures that Netflix has shared in their communication (https://about.netflix.com/en/news/an-update-on-sharing)

- They provide the option to buy a second subscription attached to the main one at a reduced price (3.99 to 7.99 USD depending on the country)

- They introduced a cheaper and “ad-supported” version in some countries, effectively lowering the adoption barrier for more cost-sensitive users

- They added a few (although basic and surprisingly missing) features to manage user accounts, devices, and subscriptions.

Are these measures enough?

Yes and no. I believe this approach is a start but is falling short at least on key 3 aspects:

- Creating the habit: A second paid subscription added to the first account means that the first account will pay more, and the second user is still not getting his hands on the wallet. This may work with young adults sharing the account of their parents, but even there… wouldn’t it be interesting to have them used to “open their own Netflix account” to start with? Think about what banks do with teenagers, who get a “free banking account”, which is nothing more than a foot in the door to become their go-to bank when they will become adults. Instead of having the “master” account pay for the “slave” account, why not have the incentive to master accounts to encourage their “shared” to open a fully paid account? Why not start collecting the email addresses of those “additional users”, in order to be able to better segment them, and give them a clear communication about how much content they’ve been enjoying on Netflix together with a more personalized experience to a first legit purchase? Why not leverage the “main account” holders as ambassadors for this transition, potentially (temporally) reducing their fee because of the referral, rather than increasing it?

- Understanding the “split the bill” UX: it’s understandable that some users are just “getting together” to split the bill. This allows them to pay a bit less but comes with the discomfort of sharing the credentials, “reimbursing” part of the bill to the main account holder, etc. What a great opportunity it would have been for Netflix to solve this pain! In the new Netflix approach, this pain goes unfortunately unsolved, so literally “higher prices, with no higher value for the users”.

- Segmentation: Putting all the users sharing in the same bucket, is neglecting that people are sharing accounts for different reasons, which shall be addressed separately. Parents paying for their kids who moved out, friends who share to get a “cheaper price”, and a grey market of people living in countries where the service is not available, or at least not with a full catalog. All different use cases and drivers may be better addressed with a more fine-graded approach.

- Pricing disequilibrium. Even if this strategy goes through, Netflix will find itself with a mass of users providing a much larger ARPU (Average Revenue Per User), that is, the mass of users who pay their subscription + the connected account. These people will remember “how much” paying the higher price hurts every time the credit card gets charged, and their churn rate will likely increase. Conversely, the ones getting the “value” out of this are still running free and will attach less value to what they’re watching (no price=no value, right?).

Time will tell, but I would have probably embraced this army of “loyal but non-paying” users in a more thoughtful “conversion” program, to move them to the full offering gradually. This may have included

- Having a more targeted approach to the different segments of people sharing: young adults who moved out, groups of friends trying to save some dollars, …

- “Balancing” the loss of a feature (the sharing feature) on the sharing account side, with another form of value for both the former “official” account holder and the one pigging back on it.

- Establishing a first step to let these new “paid users” start to pay and put their credit card number in. Even in the case of young adults, the end goal shall be to move them to become paying customers. Eventually.

Conclusion

About 13 years ago Netflix started “stealing” customers to piracy, and they did it mainly through a great user experience, affordable but healthy prices and boldly selecting customers who were willing to pay.

The move to a policy of “no tolerance for accounts sharing” makes sense on the surface, but will probably come with (unexpected) complexities in managing a new kind of user: the ones who are not used to paying in the first place. In addition, there is a non-negligible risk of making their own “premium” offers irrelevant, and pushing users to downgrade or churn.

Time will tell how much this move will be successful. My gut feeling is that it will be “somehow”, but probably much less than expected. And that additional iterations (or roll-backs?) will be needed anyway.

Wherever the truth is, it’s important to remember that pricing cannot be used just tactically. Whatever the “internal” rationale for better monetization is, it’s important to keep the user’s perspective in mind and central to the reasoning

Before you go. I like to practice what I preach, and I’d like to ask you for a very precious contribution: their honest feedback! Could you spend 2’ of your time answering a couple of very simple questions here? https://forms.gle/GgokGpEbXYtce2k58 . Thanks!

A big thanks to Roberto Borroni for challenging many of my thoughts, for their attentive review of my drafts, and for the countless suggestions for this article.

My name is Salva, I am a product exec and Senior Partner at Reasonable Product, a boutique Product Advisory Firm.

I write about product pricing, e-commerce/marketplaces, subscription models, and modern product organizations. I mainly engage and work in tech products, including SaaS, Marketplaces, and IoT (Hardware + Software).

My superpower is to move between ambiguity (as in creativity, innovation, opportunity, and ‘thinking out of the box’) and structure (as in ‘getting things done’ and getting real impact).

I am firmly convinced that you can help others only if you have lived the same challenges: I have been lucky enough to practice product leadership in companies of different sizes and with different product maturity. Doing product right is hard: I felt the pain myself and developed my methods to get to efficient product teams that produce meaningful work.